Teaching Games By Design: Making Good (Part 3/3)

The past couple weeks, I’ve talked about how to assess and categorize players’ knowledge of a game and what things tend to limit players’ engagement with your game.

Today, I’m going to talk about making your game approachable to players and how you can work within the framework of the concepts we’ve discussed to make games work for your players.

Part 3: Making Good

Part 1 Objectives

- Be able to explain what the various depths of knowledge as applied to games are.

- Be able to identify elements of a game (e.g. mechanics, setting) that require different levels of knowledge.

Part 2 Objectives

- Be able to identify and explain what players need in order to learn game systems.

- Be able to remove barriers from the knowledge-formation process.

Current Objectives

- Be able to present information in a way that fosters knowledge.

- Be able to encourage the retention of knowledge through application of design principles.

Today, I’m going to talk about making your game approachable to players and how you can work within the framework of the concepts we’ve discussed to make games work for your players.

Games that Teach

In an ideal world, your game will teach itself to your players.

Today, we’re going to look at some best practices and strategies from various games that I like.

Broadly, the two sections will talk about the elements discussed in Part 1 and Part 2 separately; the first part will talk about what you can do to foster as much learning as possible as quickly as possible, and the second part will include a few practical tools.

Part 1: Presentation is Key

One of my favorite games is Degenesis (disclaimer: I’ve worked for SIXMOREVODKA on upcoming Degenesis products), and one of the things that I think makes it so incredibly good is that it is masterfully presented.

Now, there’s a lot of things that go on here as well, like the typesetting and all of that, but we’re going to overlook that and just look at the text itself.

KatharSys, the system for Degenesis, has one of the best styles of rule presentations I’ve ever seen.

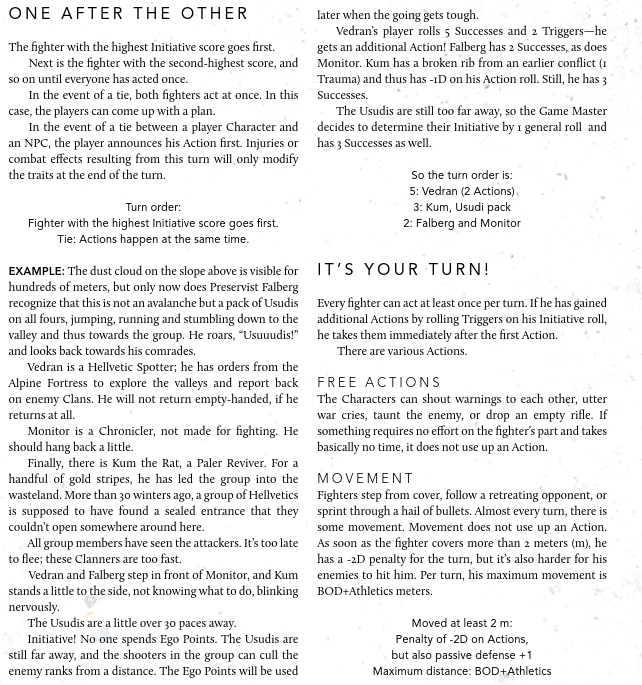

Take, for example, this excerpt from the combat section covering initiative:

I absolutely love the presentation here, and it does four things that I think are absolutely critical.

1. Headings

Headings are a killer feature that everyone sort of passively knows about but not everyone understands.

So, let’s break down what makes a good heading here:

- Communicates what’s happening in the section.

- Is clearly visible to help players find stuff on the page.

- Indicates hierarchy to demonstrate the distinction between a rule and its sub-components.

I think that this example does a pretty good job at this. It’s worth noting that I cut out part of a larger Initiative section because I wanted to get a good snapshot that showed a lot of text in its natural environment, so this is in context (which is important) that you don’t see here.

As far as visibility goes, we have a few golden elements here. There’s a different font (Avenir Roman as opposed to Calluna Regular; a sans font versus a serif font for maximum visibility), different case stylings (headings are all-caps, as opposed to regular text), and reasonably large font sizes (12 pt. for headings, 10 pt. for subheadings, 9 pt. for text; the difference is accentuated by the all-caps). There are also weight differences, with a lighter font-weight used for subheadings.

Hierarchy is important, and this has it, as we’ve already discussed. Think about presenting a bunch of bubbles for your reader, with the chapter being a big bubble and then each heading creating its own bubble within that larger bubble. Smaller bubbles let you get very specific, but also have that relationship going outward.

Organization like this is almost necessary for people to learn things, and your average audience will be conditioned to receive information in this style and subconsciously organize it (or, better yet, consciously organize it) in ways that help them make sense of it.

2. Repetition

I mentioned this in the first post, but one of the secrets to learning is that you need to give a person between five to seven exposures to a concept before something really gets embedded in their functional memory.

That’s sort of the number we use in academia because that’s the point at which students will have a good enough grasp to pull things up and apply them (e.g. you can probably expect students to use that skill at the end of the semester after they are taught at the beginning of the semester if the training goes well), but the great thing is that the sort of level of understanding and application we need in education applies pretty well to playing games.

It’s worth noting that these exposures should be spaced out; you don’t typically recall something because you see it a lot on a single day (though, again, memory is not a simple mathematical function), but you probably want three or so exposures within the learning period.

You also need to make sure that each engagement is going to be novel in the perspective of the player. Putting the same text back-to-back three times will just result in someone skipping it and mentioning that you’ve made an error.

What is really good here is the first section: it has the rules in plain text, the summary in shortened text, and then an example tied into a narrative.

3. Parallels

You’ll notice a couple things here. The rules summaries that follow the plain text have the same formatting (center-aligned, Avenir Roman instead of the Calluna Regular of the other text, slightly smaller, complete sentences optional).

Examples are marked with a leading “EXAMPLE:” throughout the text (there’s only one in this image, but I assure you that the pattern continues). The same leading element is used in other ways in places to off-set information, which helps accustom players to the distinction between different things (like requirements and effects from certain ranks in an organization), or separations between lore and gameplay elements.

The big reason why this is so important is that you want players to feel comfortable and relaxed when reading your rules. I recently saw a review of a game that said essentially:

“It was a cool game, but the format makes it really hard to read and that is a deal-breaker.”

Improper formatting can kill your audience’s willingness to engage with your game, even if it is great on its own merits. However, even with good formatting it’s still important to be consistent in your use of other navigational and layout elements. Unless things flow well you’re having players put effort into following what you’re trying to do instead of paying attention to the text.

This also helps with reference, since the reader can quickly see what parts of the text are which type of element, like finding a rule summary (for something that needs a jotted memory) or an example (for clarification).

4. Contextualization

Putting everything together in a central package is useful for contextualization. I’ve often seen games that have an example of play at the start of the book, and while that’s great as an advertising tool if people are looking at a preview online or flipping through a hard-copy at a store, it’s of limited value for actually teaching a complex game.

I actually like those leading examples, but it is worth noting that they need to be kept to a certain limit because otherwise you’ll need to repeat a lot of the same things later in context. When I think of my favorite openings to games, they generally come down to short fiction pieces (Earthdawn being my favorite example). The one exception comes from the post-Star Wars D6 games, which often included a playable solo adventure at the start of the rules, complete with baby-steps rules to get players into the game before they even have to do anything. This is a fairly large investment from a design, playtesting, and publishing perspective, but it can yield tremendous pay-offs.

In the case above, we see something that’s quite effective: rules next to examples. You don’t need to necessarily have things directly adjacent, but they should at least be in the same section. Don’t put off examples for the end of a section or shoehorn all of them at the beginning or end of the rules.

Part 2: Breaking the Barriers

Now we’ll look at the barriers and some great techniques to get past them.

1. Hook Your Audience

When I look at what draws a player to games, it’s typically one of three things:

- Some cool thing they saw somewhere.

- Familiarity with an IP.

- Word of mouth.

I’ve placed those more or less in order from my anecdotal experience. Unless you’re working on licensed games, #2 isn’t going to work for you, so we’ll just talk about the first and third elements here.

The first step to getting your game to be that cool thing a potential player saw somewhere is to have it be out there.

The second is to have it be a cool thing.

Getting your game out there is a much easier topic to bring up, and there are really three pillars to that: marketing your game, building a community, and handling the product line.

Marketing the game is the most tricky part here, and the truth is that it probably changes from time to time. We might see it stabilize as digital marketplaces and social media platforms standardize, or we could still see rapid change for the next decade or two.

I’ve released games through DriveThruRPG, and it includes some of its own tools to let you do on-platform marketing and advertising.

Other platforms, like itch.io, provide less marketing (in part because they may be more broad or niche than DriveThruRPG, which primarily focuses on traditional RPG products), but in any case you’re probably going to get most of your marketing from social media. I’m not an expert on that, but I will say that it rewards a mixture of time, effort, and luck.

Building a community around your games is absolutely key, and you can use platforms like Discord to do so in a way that permits productive conversation (e.g. immediate access to you, moderation, and a concentrated stream of information). Reddit works well, too.

The secret here is to engage and reward the community. It goes beyond just providing a space and requires you to provide content and updates. Make good on those, and you’ll build networks of loyalty and trust.

Finally, you need to think about product lines, either as a broad design sense (e.g. you probably don’t want to be a one-hit wonder) or within a particular intellectual property or game.

You want to make sure that your basic products are available at a level that draw people in (free or cheap; around $10 seems to be a good number for a full-fledged introductory experience, but that’s for a professional or high-quality indie experience).

This might be something like a quick-start guide for an RPG, or a basic deck in a collectible card game. I’ve got the R. Talsorian Games Cyberpunk Red Jumpstart, and it’s more or less exactly what you would want, though it’s perhaps on the meaty end of things with both a setting focused book and a rules focused book.

Print and digital are important to consider. Give something away as a free download, and people will be able to access it immediately. That should be an experience that takes people into your game, even if it doesn’t delve the depths.

If you want players to play your game, however, you need to consider the print market. If you don’t have a desire to publish your game in print, or if you want players to have the option to do their own printing in addition to your own, then make sure that you have easily printed documents (black and white, concise, standard format).

If you do want to publish in print, you need to think about how you can deliver that product effectively. If you have a box with a rulebook, board, cards, and the like, you’re going to start pricing out customers fairly quickly. Even a rulebook can quickly become cost prohibitive.

If this is the case, think about how you might try to deliver an experience that is representative of your game at a price point that can lure in the curious.

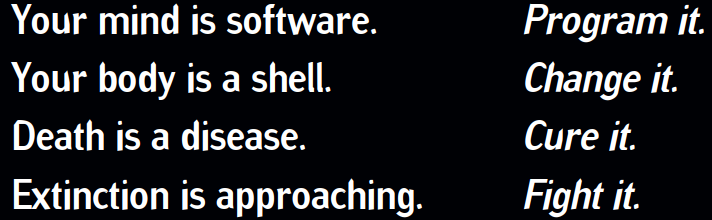

The Power of a Statement

One thing that I cannot stress enough is that it helps to have some way to quickly and easily communicate the major ideas of your game.

This is important for two reasons.

A statement can very easily encapsulate the theme of a game.

This is from Eclipse Phase, which is an incredibly high-concept transhuman science fiction roleplaying game. These four lines are the defining statements of the game and what the players will (ostensibly) be trying to do with their characters in the game.

Another strength of a statement is that it can serve as a realigning factor and a way to get everyone on the same page. Savage Worlds’ “Fast! Furious! Fun!” description keeps everyone on the same page with regard to system goals, in addition to just being a memorable tagline that can draw people in.

2. Be Conscious of Your Audience

Think about what people need to get into your game, and provide it.

I’ve seen a lot of games that have either multi-hour setup times, massive rulebooks, or complicated mechanics that put people off.

Think about what your audience wants and needs, and if you’re delivering that well.

This doesn’t mean you need to create a simple game. Complex games attract their own sorts of players, but you shouldn’t make a complex game for a casual audience.

I think of Magic: The Gathering as a good example of a game that has a nice balance between simplicity and complexity. Learning to play is easy; turn cards to produce mana, use mana of certain colors to play certain cards, once a turn you can attack with creatures.

Of course, that’s a gross simplification, but the general concept itself is pretty simple (and other games that have followed it, like Keyforged, often streamline some of the processes further), and the system allows a lot of blossoming outward.

Think of the core experience and the full experience as two separate elements.

Steve Jackson’s GURPS has a reputation for being complex, and while I’d like to say it’s largely undue I have to confess that I’ve never been able to make it through the full core rulebook without getting burned out, and I used to go through core rulebooks like no tomorrow when I was younger and had more free time.

However, GURPS Lite comes in at about 32 pages, and it’s one of the most easily comprehended rulesets out there because it takes the core experience and condenses it down to just what a player needs to understand the core game.

One of the things that I often see designers do is write from a perspective of knowing their game and put things on paper that don’t make sense to their audience.

I’ve been that designer, too.

One of the frequent pitfalls in game design is taking something a designer has figured out (or at least mostly figured out) and putting it into a form that jots their memory, but doesn’t make itself accessible to others.

A lot of designers have generalized knowledge of how games work that is not immediately applicable to the broader public, and sometimes that knowledge is nuanced and complex. The context that a designer comes from can shape a good deal of how they approach their work, but an asset can become a weakness when it leads them to overlook the necessary steps to get to a game that players can understand.

Ultimately, the way to do this is dependent on a bunch of different factors and the type of game you’re creating, but I’ll leave you with one simple piece of advice.

If it needs a diagram, get rid of it.

If you can make a diagram of it, make that flowchart available to players somehow.

Closing Thoughts

A good game gets people talking, but a great game gets people playing.

The number one job of a designer is to make a game playable and appealing, and if you want to design a game the first step to that is making sure that people can learn to play it.

Think about the core essence of your game, and present it in multiple ways. Design the play experience so that rules are reinforced during play, and that there is a generalized principle between the rules that gives players fresh perspectives on each rule as they interact together.