Respecting Player Interest in Roleplaying Game Design (2/3): Communication

In Part 1 of this series, we talked about using a theme and concept to center a game on what players are interested in. Today we will talk about how to use communication strategies–both in-text and in marketing–to link your game to particular player interests.

Communication

If you make a game that is tremendous and focused on something that it does really well, you still need to make sure that players know that’s what the game’s about.

The central point here is to build clarity and brand your game so that players know what to expect. This gives a better experience for everyone playing the game, and keeps people from feeling ripped off if they spent money on your game and then discovered that it doesn’t offer the experience they expected.

Building Clarity

One thing that helps is to make sure you have a very clear emphasis on what your game is about. You want your examples and statements to reflect the absolutely most significant element of the game.

Going back to the focus, you need parts of the game that are going to directly emphasize your focus so that players can align around the same central point.

Description

A solid description of the game is one of the best ways to get players sold on the game.

However, it needs to be clear, coherent, and bold. If the focus is absent, the description’s utility is lost.

Take Dungeons & Dragons as an example:

The Dungeons & Dragons roleplaying game is about storytelling in worlds of swords and sorcery. It shares elements with childhood games of make-believe. Like those games, D&D is driven by imagination. It’s about picturing the towering castle beneath the stormy night sky and imagining how a fantasy adventurer might react to the challenges that scene presents.

I think this might be one of the weakest introductory paragraphs in a role-playing game, and I think it speaks to something that is a problem with Dungeons & Dragons’ focus (or lack thereof).

This is only part of the introduction, but past this point introduction is focused on explaining the game rather than explaining the focus of the game.

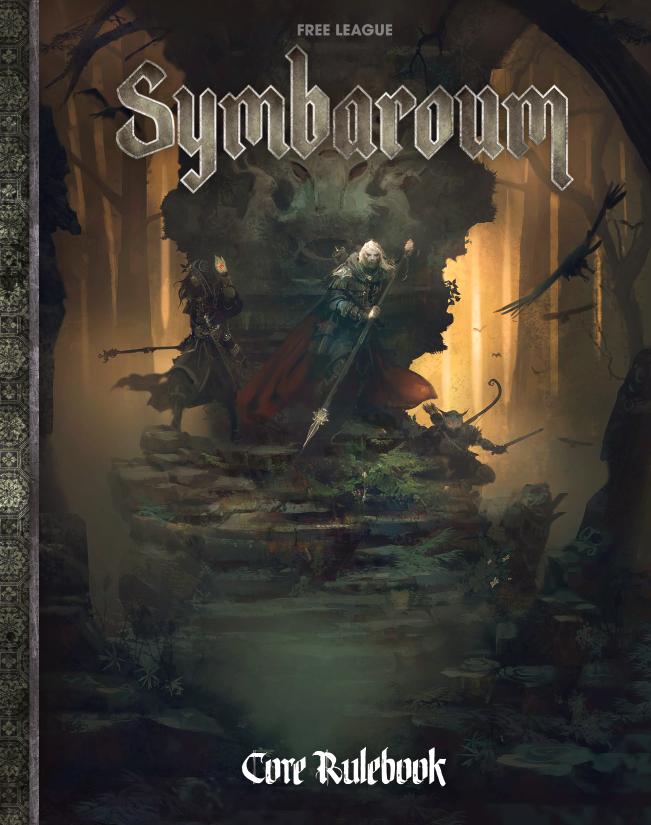

Now compare it to Symbaroum, a game that is mechanically fairly similar to Dungeons & Dragons, despite major thematic differences.

Symbaroum is waiting for you and your friends! The book in your hands is more than mere paper and ink. It is the gateway to another world; a world where you will get to explore the vast Forest of Davokar in the hunt for treasures, insights and fame; where you may visit one of the eleven barbarian clans to trade or to plunder their treasuries; where you can establish a base of power among princes, guilds or rebellious refugees in the capital city of Yndaros; where you can fight for the honor of Queen Korinthia or ally yourselves with the ancient guardians of the forest. Whichever path you choose to walk, unforgettable adventures are waiting behind every crest and bend.

Obviously this is a longer introduction, which gives it a little more room to be detailed and specific.

However, there is a different nature to what players are getting from the two introductions.

In Dungeons & Dragons the clearest communication that we have regarding what the central focus and thrust of the game is is that its “about storytelling in worlds of swords and sorcery.”

Fans often say that a selling point of Dungeons & Dragons is that it can present a broad variety of worlds, which raises two questions here:

- What is swords and sorcery as a genre?

- What sort of storytelling are we doing?

The breadth of experience comes at a cost of poor definition, so players often enter D&D with different expectations of what they will get out of it. Worse, the intro here doesn’t define these terms here or later, or give very specific examples that might be familiar to players new to the game. Later, it does use D&D-related settings as examples, but players are unlikely to be intimately familiar with them, and these settings are used to dress up the examples instead of being explained in examples themselves.

Symbaroum doesn’t raise questions. Instead, there is a clear focus on what players will do: hunt for treasures, visit barbarians, establish a base of power, fight for honor, and/or ally themselves with the forest.

That’s broad as far as focus goes, but it has less ambiguity than the Dungeons & Dragons example. You don’t have to define genre or set tones for storytelling because that’s done without falling back on players’ individual understandings of genre and tone.

Fiction

Quality fiction can serve as a trailer for what your game features.

To give an example, let’s look at Earthdawn.

To my knowledge every edition of Earthdawn starts with the same short story, a piece called Inheritance. It’s eight or nine pages long, so it’s more than you necessarily would have in an indie game, but it does a tremendous job of painting a scene that’s based on play. Opening with fiction is a great option for achieving clarity without needing to do a lot of communication regarding terms and genre if your game will be doing things that are not necessarily familiar to the players.

If you’re curious, there is a preview of one version of Earthdawn on DriveThruRPG that features the full text of the “Inheritance” short story.

It still helps to have some intro following fiction if you start the game off with fiction. Not every game has fiction, but I think that games with fiction tend to have a much better shot at hooking players on their universe, perhaps at the expense of selling players on play itself.

Examples of Play

Examples of play follow the actual rules and mechanics of the game through the scene and narration style that you have set.

The obvious strength of an example of play is that it helps to clarify the rules as well as the storytelling style that you’ve built up with your game, but there are a few potential downsides.

The first is that placing an example of play is difficult. It can serve two purposes: clarifying interests or clarifying mechanics.

In the first case, it makes sense to have the example of play early in the book, but this has its own downsides.

- It can look a lot more difficult than it really is because it comes prior to any explanations.

- Managing the length relative to exposure can be difficult.

- A quality example for clarifying interest may not clarify mechanics and can actually confuse them.

One of the greatest sins I’ve seen in examples of play is the production of a 90’s action figure advertisement vibe. There is a small set of circumstances in which this would be acceptable, but generally it’s not feasible.

Another thing with the example of play is that it’s hard to highlight an iconic element of the setting in an example, in part because you’ll have more mechanics here (we’ll go into more depth about that in Part 3, though we covered it some in Part 1). This is largely a genre thing. It would be trivial to write an SLA Industries example of play that highlights its splatterpunk setting because you just focus on extreme over-the-top violence.

For examples of play that clarify interests, consider streamlining the gameplay elements; give a blow-by-blow and not an explanation of how the mechanics are unfolding under the hood. Going back to D&D, this is how they do it, and I think it’s the best part of their intro: they present the example of play as a dialogue with stage directions, not a detailed account of the dice, numbers rolled, GM decisions unfolding, and the like.

If you need a lot of examples to illustrate your mechanics, partition those examples to show off your rules in the appropriate places, usually after you’ve explained the rules. Don’t try to double-dip on clarifying interests and clarifying mechanics.

Branding

Branding is difficult and has a lot of overlap with things that are not in my wheelhouse, but there are a few quick points I’m going to make:

If your cyberpunk game is an introspective take on the role that machines play in our lives, and the cover has a cyborg murder-machine with an .80 caliber handgun with smoke pouring out of its barrel framed by hyper-saturated shock colors and a ragged font, you’re probably not branding it to meet your target audience.

Likewise, character in a pose is a low-information option for a cover. Character in a scene works better.

Branding applies to all the marketing copy you use, not just visual elements. If you sell your game with one cool dramatic event, it had better be something that the game focuses on doing; fiction that can’t play out in-game is not helpful when it comes to earning player trust and loyalty.

There is something to be said for clarity, and another thing to be said for visual appeal.

Case Study: Symbaroum

This is a character in a scene for the cover, and it works really well. Note how there’s a blend between characters and the surrounding scene; this centers on the figures but it’s also turning the setting into a character.

Color and tone are important here as well; Symbaroum is dark fantasy, and the muted colors play into that vibe. However, there’s the gold in the background that speaks to a sort of glory and majesty; it’s not all lamentations and mourning, with splashes of both light and high-saturation color. In fact, it’s not even terribly dark; a lack of saturation creates the feeling of darkness and lets the vibrancy of the characters and particularly dark elements stand apart from the unimportant bits.

The font and the sidebar both contribute to letting you know what the game is about as well; this screams dark fantasy from start to finish.

Case Study: Degenesis

Consider this cover, for a book that I worked on, a supplement to the roleplaying game Degenesis.

Degenesis generally has abstract covers that have a symbolic relationship to their content at best, but it stands out next to other books.

A potential weakness here is that nothing about this book gets terribly specific. If you’ve never heard of Degenesis before, take a moment and guess what genre it falls into.

Did you guess post-apocalyptic with sci-fi elements?

This was a deliberate decision; go abstract and maximize visual appeal, and let the quality of the image draw people in.

What Design Works for Me?

Consider what you want to do with your designs carefully, but there’s not necessarily one correct answer.

The important thing with branding is that if you mislead your players, they’re going to start off on the wrong foot.

Symbaroum lets you know exactly what’s in it by its cover. However, as pretty as it is (and I chose it because it’s a great cover), it’s still not in a league of its own.

Degenesis is abstract until you get into the rules content and then it’s skulls and splatters and grit and mystical poetry about the end of the world.

Wrapping Up

Previously, we looked at themes and concepts, and today we talked about communication.

These are both key parts of making sure that your games speak to players and focus on what they want to see. However, as a game designer you have another job ahead.

In Part 3 we’ll move in to a deep dive on how to use mechanics in a way to respect your players’ interests and make a game that lives up to its promise.

K is the Head Honcho of Loreshaper Games; you can find more of his writing on Hive, and his games are available at itch.io and DriveThruRPG.

One Response

[…] Part 2 of this series talks about how to communicate the central ideas of your game to align player interest. In Part 3, we focus on making sure that the mechanics match the promise of the game. […]